BLACKWELL, Okla. – On a warm, sunny April day, the breeze is refreshing across the former Blackwell zinc smelter property. The air smells clean. The moment is surreal and suggests no danger.

A quick look around takes one back to the sound of the whistle calling workers to work, the clackety-clack of the train engine rounding the bend and the scurrying feet belonging to hundreds of fathers, brothers, grandfathers and uncles.

Smelter Heights is alive on this particular spring day. Its breath whispers to each and every person who passes by, and those who stop and listen might just hear a few secrets. At the very least, they will learn something about loyalty, dedication, hard work, war, economics, corporate influence, money, division, challenge, teamwork and the foundation that set its stakes in Blackwell long ago and refuses to leave.

Leaving is not really an option for this resident. No one else would want a neighbor like this.

This resident came to town in a whirlwind and put on a convincing face. It brought jobs. It brought prosperity. It brought dreams to life – just like any good neighbor would.

Then the neighbor got greedy. It started stealing from a few families. It brought sickness for some and wealth for others.

It worked so hard for so long. It made its fortune and decided to quit. Many did not understand. Many were thankful. Many were just wondering how they would feed their families.

Jobs, prosperity, and the American dream

Deana Walter remembers her father coming home from a hard day’s work at the Blackwell zinc smelter. His nickname was “Red,” but it wasn’t because the heat of the smelter made one side of his face appear sunburned all the time. No, Walter “Bud” “Red” Padgett had red hair and was proud of it. And, like most red heads, Padgett was fair skinned – not the ideal skin type for working in a zinc smelter.

But he went to work every day, and Deana helped wash his blackened clothing and hang them in the smoke-filled air to dry.

Even though she remembers her father dog tired and not always in the best of health, she still smiles when she thinks about some of his stories – like the time the “guys” tried to determine how hot it really was inside the smelter.

“My dad found a thermometer that went up to 3,700 degrees,” she said. “And it melted.”

When she was in elementary school, she got to see first-hand just what her father endured day in and day out, but she wishes now she would have paid more attention.

“Do I remember much about it now, not really,” Walter said. “Other than it was terribly hot.”

The heat she felt was nothing compared to what her father experienced.

“They wouldn’t let us get very close,” she said. “I don’t really think that people realized how dangerous it was. It was kind of like going to hell.”

Walter’s visit took place in the 1940s, just before the smelter’s ultimate heyday, and not long after its struggle to stay afloat.

A war gave birth to the steely giant; a depression darn near killed it, and a second war nursed it back to health. Along with its own fortitude, the smelter saved hundreds of young men, like Red Padgett, from going to war – at least on foreign soil.

The bittersweet beginning and end of the Blackwell zinc smelter

Wartime swept through Oklahoma in 1916 quicker than any prairie grass wildfire. The state was rich in minerals, natural gas and ore. Uncle Sam needed everything he could suck out of good Mother Earth, so of course the logical choice was to come to God’s country.

Dozens of mining facilities went up in a matter of months. The newly founded state, which was undeveloped territory nine years prior, welcomed the growth and job opportunities. It was a proud moment for the Sooner State. The war depended on Oklahoma, and thousands were anxious to chip in.

According to county land records, Theodore E. Kaufold deeded his property over to the Bartlesville Zinc Co. on March 3, 1916. He raked in more than $25,000, not bad for a piece of land for which Elias Allen paid $1 on Aug. 13, 1897.

Perhaps the zinc smelter property does not boast the earliest recorded purchase of land in Kay County, but it certainly could compete for having the most entries.

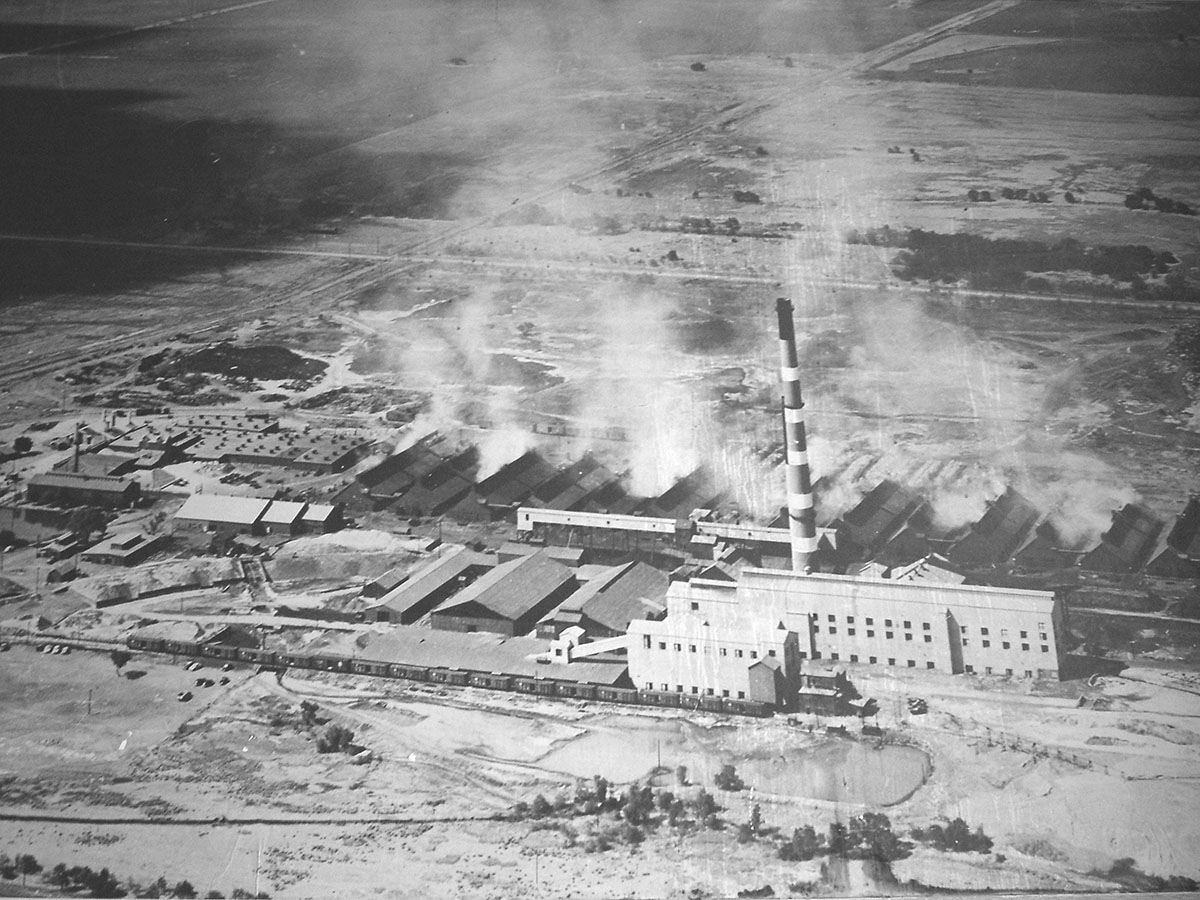

When Bartlesville Zinc officials decided they wanted to build a smelter, they built it. Ground was broken March 25, 1916, and in less than 80 days the smelter had all the materials it needed on hand. The Atchinson, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway wasted no time in building a spur that conveniently ran alongside the smelter, and the land provided enough minerals, natural gas, zinc and coal to keep any mining company in business.

The smelter put 187 men and women to work right off the bat.

Prosperity kept coming, and Bartlesville Zinc decided it was time to share the wealth. The company sold its smelter site Nov. 10, 1922, to Blackwell Zinc Co. for nearly $136,000, and Blackwell Zinc put more men to work.

Many of them lived in Smelter Heights, close enough to hear the whistle blow at 3 a.m. each day. It blew again at 5 a.m., signaling the time to open the furnace. At 7:30 a.m., the men knew it was time to get on the job, and at noon, the quitting time whistle meant a welcome break. Workers went back to work at 12:30 p.m., and the 4 p.m. whistle told them to go home.

For some, that meant just a short walk. For others, it meant a longer walk, but it was a walk that took them to their new homes in their new town.

Blackwell boomed, just as the smelter did. Residents began building homes and businesses east and north of the smelter – just downstream, where their prosperity and founder would later seep in to haunt them.

Supplies kept coming in, and workers kept pounding out galvanized iron and steel products, like utility water piping, windmills, water tanks, siding, roofing and even lightning rods.

Then the war ended, the stock market fell, and the smelter met its match. It faltered, but only briefly during the early stages of The Depression.

It rose from the ashes on New Year’s Day 1933 and breathed life into the Blackwell community with a vengeance. Blackwell Zinc and its employees flourished through the ‘40s and ‘50s under the direction of Amax Corp., a subsidiary of American Metal Company LTD.

The erection of a new sintering plant in 1951 only propelled growth and led to the 1957 opening of the adjoining cadmium plant, which churned out products used in paints, pigments, ceramics, television phosphors and chemical compounds.

The company also turned to revolutionary new inventions, like machinery, “to lighten the burden for the smelter workers and provide greater safety for him and his job,” according to Amax officials in a 1966 promotional magazine.

The same officials wrote, “Blackwell employees, like their counterparts, the American worker in (the) manufacturing industry, have shared in a better standard of living brought about by the growth of the American economy over a 50-year period.”

By 1966, more than 835 employees were enjoying paid vacations, paid holidays, life insurance, pension plans, accident benefits, disability insurance and paid sick leave.

Little did any of them know how much they would need the incentives.

The Blackwell zinc smelter had grown into the largest horizontal retort furnace in the United States. The facility itself covered 80 acres, and the company owned 700 acres of land surrounding the plant.

New developments, like the sintering plant, helped the automobile industry to become the largest user of zinc in the form of galvanized steel and zinc diecast products.

Workers were making large corporations’ big money, while families were starting to realize the burdens of such a task.

The health hazards of a zinc smelter started filtering into the community that had built its livelihood around it. It was time for the smelter to leave its permanent mark because by the late 1960s its glory days were through.

A group of farmers started noticing unhealthy, barely harvestable crops. Workers began feeling the effects of breathing toxic waste all day long, and the federal health authorities’ phones were ringing off the wall.

Still, others wanted to keep their jobs. Their families depended on the smelter.

Town divided over Blackwell zinc smelter

Blackwell Zinc Co. officials would never officially blame the closing of the smelter on a group of hardnosed farmers, but a lawsuit was filed in 1971, and the company announced a tremendous downsizing shortly thereafter.

“The obsolescence, combined with the recent pressures of environmentalists forced the Blackwell Zinc Co. to a decision to phase out its Blackwell plant,” said a plant official in an article from the Blackwell Journal-Tribune.

The final door closed in the spring of 1974, and the farmers, along with several workers, won their $4.8 million lawsuit, and Blackwell Zinc was told to clean up the mess.

Red Padgett was one of the workers who was compensated.

“My dad got part of that settlement,” his daughter, Deana Walter, said. “My dad wasn’t always sure he should have taken the money.”

And that conveys the loyalty of most of the smelter workers. Many of them still gather on an annual basis to talk about the good old days.

Some could tell stories about the virtual riots between those who filed the lawsuit and those who remained faithful to the smelter.

As for Blackwell Zinc Co., it’s not clear what happened to their namesake. Officials handed the deed to the property over to the Trustees of the Blackwell Industrial Authority on Dec. 17, 1974.

Actual ownership of the property becomes somewhat unclear after this time period.

Freeport-McMoran Copper & Gold Inc. claims to own the land, having “inherited” it when the company acquired Phelps Dodge in March. Phelps Dodge officials contend the property was purchased from Cyprus Amax in the late 1990s.

County land records show no transfers of deeds to any of the companies, and county records turn up nothing on the companies, either.

It is possible the companies have leased the land, but if so, none have paid ad valorem taxes, from which the Blackwell Industrial Authority, a public trust, is exempt.

Many of the outlying pieces of the former landfill have been sold or leased over the years. Right-of-ways have been granted for utility companies, and industries have come and gone.

County land records show transactions to Southwest Corset, Los Angeles Boiler Works, Electron Corp. and several industries that remain in operation in the Blackwell Industrial Park today, but no records indicate Cyprus Amax, Phelps Dodge or Freeport McMoRan ever set foot on the properties.

Three calls were made to the Blackwell Industrial Authority office to inquire about the arrangement, but BIA Executive Director Shane Frye had not returned phone calls by press time Wednesday.

Who is Freeport McMoran?

Take a look at their Web site, www.fcx.com: “Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. (“FCX”) is an international mining industry leader based in North America with large, long-lived, geographically diverse assets and significant proven and probable reserves of copper, gold and molybdenum.”

The company acquired Phelps Dodge on March 19 to “create the world’s largest publicly traded copper company. The combined company has geographically diverse, long-lived reserves in copper, gold and molybdenum.”

The company recorded revenues in 2006 of more than $5.8 billion and a net income of more than $1.4 billion. More than $1 billion was returned to shareholders last year.

Freeport McMoRan apparently took over the responsibility of the smelter clean-up when it acquired Phelps Dodge and has proposed recently to install a $5 million groundwater treatment plant to contain and monitor toxic cadmium components that the smelter waste continues to seep into the city’s groundwater.

The company also has opened a local office on East Blackwell Avenue, in the former Arkla Gas Co. building, to field local questions and monitor progress.

The city recently hired an outside attorney to help resolve environmental issues. Freeport McMoRan is paying for the legal services.

Officials stand behind the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality’s conclusion that the outlying property was cleaned up properly before Phelps Dodge’s takeover in the 1990s.

Conflicting reports from an environmentalist hired by a Texas law firm, however, suggest something else.

Who is Nix, Patterson & Roach?

“Nix, Patterson & Roach L.L.P. is one of the premier Plaintiffs’ law firms in the United States,” taken from www.nixlawfirm.com.

A simple Internet search will reveal that founder Harold W. Nix was part of the Big Five, a group of underdog lawyers who went head-to-head with the tobacco industry for the state of Texas – and won.

According to an article published Nov. 26, 1999, in The Texas Observer, “The lawyers took the case with poor prospects, risked between $40 and $50 million of their own money and won the largest settlement in the history of civil litigation – $17.3 billion,” although collecting the money was perhaps the biggest battle of all.

Still, Nix’s name can be seen every day at Baylor University in the Harold & Carol Ann Nix Academic and Advocacy Center, which is the east wing of the Sheila and Walter Umphrey Law Center, Baylor Law School. Umphrey was another member of the famed Big Five.

Nix also is listed at No. 25 on the Mother Jones Top 400 list of campaign contributors. With the additions of partners Cary Patterson and Nelson Roach in a tied position at No. 125, the firm is reported by the Center for Responsive Politics to be the second largest soft-money contributor to the Democratic Party, donating nearly $750,000 in 1999 and more than $1.6 million in 2001 and 2002. Much of the funding is donated to politicians working against lawsuit reform advocates.

(CRP reports that in 2006, Phelps Dodge Corp. donated $181,685 to federal candidates, with 84 percent being donated to the Republican Party and 16 percent going to Democrats. The company was the fourth largest donor in the U.S.; Freeport-McMoRan came in at No. 5, donating $180,600, with the same percentage breakdown as Phelps Dodge.)

Roach, along with attorney Keith Langston, an attorney with the firm out of Daingerfield, Texas, has made several trips to Blackwell, including a recent trip April 12 to meet with residents who are concerned with possible lingering smelter contamination.

The attorneys said they hired environmentalist Dr. Rod O’Connor to perform tests on soil and dust in several homes throughout Blackwell.

Test results were revealed at the public meeting, and O’Connor said the results indicate lead levels exceed Environmental Protection Agency standards and that Blackwell residents are facing a potential crisis.

The attorneys encouraged residents to continue searching for facts they claim Freeport McMoRan is hiding.

The attorneys also conducted interviews with local residents several weeks ago in an attempt to collect more data about the smelter fallout.

The attorneys have not filed any lawsuits, but they have indicated the possibility in the future.

Their case will rely heavily on the tests performed by O’Connor, and their motives are sure to come under fire with many who remain unsure about the smelter contamination.

Skeptics may claim the attorneys could be part of a growing epidemic of environmental lawsuits popping up across the country.

An article written by John M. Wylie II and published in the January issue of Readers Digest, outlines “The $40 Billion Scam,” where attorneys use qualified experts to testify in cases against big-name corporations in lawsuits where billions of dollars worth of claims are filed.

The firm of Nix, Patterson & Roach was in no way linked to the article or any of the lawsuits that took place.

Who is Dr. Rod O’Connor?

Dr. Rod O’Connor is a 1955 graduate of Southeast Missouri State College. He received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics and received his Ph.D. in physical organic chemistry in 1958 from the University of California at Berkeley.

His resume reports that he has worked with at least 36 consulting clients; 12 governmental agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Army Toxic and Hazardous Materials Agency; and 55 law firms with defense cases on environmental issues.

His methods were questioned last year during a trial in Prairie Grove, Ark., where the Louisiana law firm of Lundy and Davis sued Alpharma, the makers of a chicken feed found to contain Roxarsone, a cancer-causing agent. The law firm lost the case but appealed in March.

The findings of the tests he performed in Arkansas were published in the Journal of Environmental Forensics.

After conducting the tests in Blackwell, O’Connor sent a letter of notification to Cheryl Barr, program coordinator of the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program for the Oklahoma State Department of Health.

“After receiving the final results, I discussed this case with a friend who is an environmental and public health medicine specialist,” the letter reads. “He suggested that the lead loading results, coupled with the elevated arsenic levels, might represent a public health problem of considerable urgency. It was at his suggestion that I contacted your office.”

At the April 10 public meeting conducted by Freeport McMoRan, Barr was present and said the blood lead levels from 2000 to 2006 for Blackwell children six years old and younger indicate a slightly higher average than the state average.

She said lead exposure most likely came from lead-based paint in older homes, which make up more than 50 percent of Blackwell’s housing.

She also encouraged anyone worried about a child’s blood lead level to have the child tested.

“(Speaking) as a mother and a grandmother, anybody who lives in an older home should be tested,” she said.

What’s next for the Blackwell zinc smelter?

Freeport McMoRan will begin soil samplings in June for anyone concerned with lead or arsenic contamination on outside properties. Attorneys say voluntary sampling is not good enough and will not permanently fix any problems. They also contend that cleaning up outside properties will not affect contaminants that may be inside housing units.

Freeport McMoRan also will move forward on the construction of the groundwater treatment facility.

Attorneys for Nix, Patterson & Roach said April 12 they will continue to pursue the issue and collect more data as issues unfold.

Attorney Nelson Roach encouraged citizens during the meeting to team up to protect their community.

“Every one of you is in the same rowboat,” he said. “Are you going to row the boat or drill a hole in the boat?”

He said in order for Blackwell to grow, problems need to be addressed.

“Businesses aren’t coming to Blackwell because businesses aren’t yet convinced that this town is cleaned up,” Roach said. “Blackwell is going to live or die based on whether Phelps Dodge is going to clean this town up.”

Many residents said they have accepted the challenge and want to do what is best for Blackwell and its residents, but perhaps long-time resident Diana Whitman said it best: “We can do it because Blackwell people are strong. It’s time that we make it happen.”